Abner Doubleday has for years been considered to be the man who invented baseball. But the fact is he was a military man with no ties to the national pastime.

That is…until after his death.

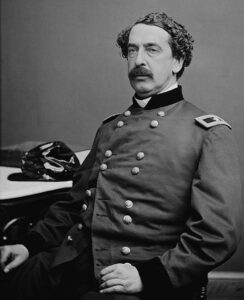

Military Man

Doubleday came from a military family. One grandfather fought in the Revolutionary War and another was a messenger for George Washington. His father fought in the War of 1812 before spending four years in Congress.

So after attending a preparatory high school in Cooperstown, New York, it wasn’t unusual when he attended the U.S. Military Academy at West Point from 1838 to 1842, graduating 25th in his class of 56.

His first notable contribution came at Fort Sumter, sight of the first battle of the Civil War. He fired the first defensive shot for the Union when they came under attack, effectively signaling the beginning of the war.

He worked his way up in rank throughout the Civil War until in 1863 when, as Major General, he assumed command of the 3rd Division, I Corps following the death of General John Reynolds at the Battle of Gettysburg.

Under the leadership of Abner Doubleday and others, the troops were able to fend off Robert E. Lee’s overwhelming Confederate forces during the first day until reinforcements arrived. However, he wasn’t given permanent command of his corps and suffered a neck wound on the second day of battle.

The Union army was eventually able to defend the key positions of Cemetery Ridge, Cemetery Hill, and Culp’s Hill and help turn the tide of the Civil War.

Doubleday then spent time in Washington, D.C., San Francisco (where he patented the cable car system), and Texas before retiring in 1873.

Before his death early in 1893, Abner Doubleday helped manage Gettysburg National Park and also published two Civil War books.

But in 1907, more than 14 years after he had died, his legacy would take a strange turn.

Baseball Man?

Baseball entrepreneur and executive Albert Spalding was looking to settle a dispute with the famous baseball journalist and promoter Henry Chadwick.

Chadwick contended that the game of baseball had developed from the English game of rounders. But Spalding insisted that the game had American origins.

So in 1905 a commission was organized by Spalding, known as the “Mills Commission” after its chairman, Abraham Mills, in order to investigate the invention of baseball.

They put out a “call for people who had knowledge of the beginnings of the game” and got the kind of response they were looking for from a 71-year-old man named Abner Graves in Denver, Colorado.

After receiving a letter from Graves, the Beacon Journal in Akron, Ohio published a story entitled “Abner Doubleday Invented Baseball” which told the supposed details of baseball’s invention in 1839.

According to his letter, Graves had attended school in Cooperstown with Abner Doubleday and witnessed his invention of the game of “base ball” and his drawings of a baseball field in the dirt.

The Commission didn’t interview Graves but still used his claims as its primary resource when they issued their “finding” on December 30, 1907. They declared that, according to the “best evidence” available, American Civil War hero Abner Doubleday had invented baseball, the baseball diamond, and baseball’s rules in 1839.

The Problems

The Commission, however, failed to address some critical problems with Graves’ story.

- Graves would have only been 5 years old in 1839. How many people can accurately remember anything they witnessed at that age?

- Doubleday was enrolled at West Point in 1839 and there were no records that showed he took any leave.

- Despite leaving extensive writings and publishing two books, Doubleday never mentioned the game he supposedly invented despite its growing popularity by the time of his death in 1893.

The reliability of Abner Graves’ story became even more questionable a few years later when mental illness drove him to kill his wife and spend the remainder of his life in an asylum.

Also, over the years historians have been able to find references to “base ball” as a children’s game before 1839, even as early as the 1700’s.